A product’s packaging often accounts for only about 5% of its total climate impact — but that doesn’t mean it’s unimportant. Using less plastic, biodegradable materials or recycled paper might seem like obvious sustainability solutions, but product production and waste typically have a much greater impact. The right packaging can actually enhance a product’s sustainability by reducing waste, extending shelf life, or improving transport efficiency. In this article, we show how packaging can be both minor in impact and crucial in function, while the packaging industry as a whole still holds enormous potential for sustainability improvements.

Calculating climate impact with a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a detailed picture of a product’s total impact, including its packaging. LCA is a method that calculates a product’s overall environmental footprint — from raw material extraction to waste processing. Packaging components such as cardboard boxes, plastic wrapping, or foam fillers are all included in this calculation. With an LCA, you can make data-driven decisions instead of relying on intuition. Interestingly, these analyses often reveal that packaging has far less relative impact than we might initially think.

An important aspect of LCA is that it doesn’t only measure CO₂ emissions, but considers a broad range of environmental effects. For packaging too, the entire chain is analysed — from material production (e.g. melting sand for glass) to transport, use, disposal (recycling, incineration, or landfill) and, of course, the packaging of the product itself.

Packaging as “Low-Hanging Fruit”

Our calculations for clients show that packaging contributes relatively little to the total climate impact of a product — often between 5% and 10%, depending on the product. Less than many expect, yet still important in a climate analysis. That’s because packaging often represents “low-hanging fruit”, an area where improvements are relatively easy to achieve.

Of course, when we talk about packaging here, we mean in relation to the product. The packaging industry as a whole is vast and often single-use by nature. Single-use means it’s thrown away after one use — a waste of valuable resources.

For many companies, optimising packaging is an accessible first step to reduce their footprint. The “R-ladder” of the circular economy provides a useful framework for making packaging more sustainable:

- Refuse & Rethink: Is the packaging really necessary? Sometimes product design or logistics can be adjusted to reduce or even eliminate packaging. The most effective sustainability measure is often simply to avoid unnecessary packaging.

- Reduce: Use less material for the same packaging. A thinner layer of plastic or a smaller box can already make a big difference without compromising protection.

- Reuse: Choose reusable packaging, such as deposit bottles or crates within logistics systems.

- Recycle: If the above steps aren’t feasible, design the packaging for recycling. Use materials that aren’t mixed with others, so they can be easily separated and processed. Contamination, for example by inks or mixed plastics, is often the biggest barrier to successful recycling.

For small and medium-sized businesses, Reduce is often the easiest place to start. It not only benefits the environment but can also reduce costs directly.

Beyond plastic: a look at different packaging materials

The debate about packaging is often dominated by plastic, but many other materials play important roles. Glass, cardboard, metal, aluminium, and biobased plastics all have distinct environmental impacts. It’s crucial to take this broad view, since the ecological footprint begins at raw material extraction: trees for cardboard, sand for glass, oil for plastic. Production, transport, and post-use processing, whether recyclable or not, also determine the overall impact.

Each material has pros and cons depending on it functionality:

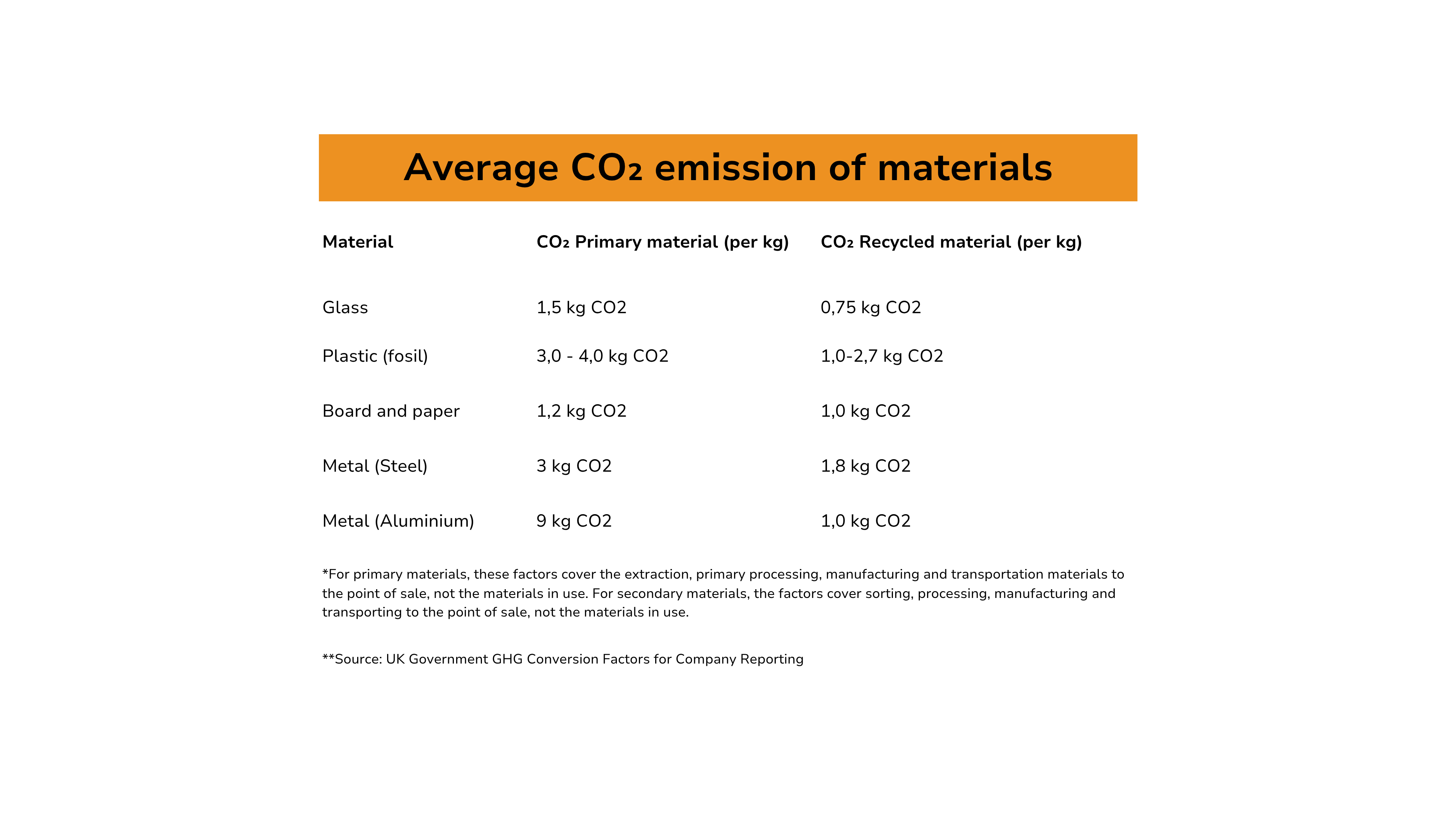

- Glass: Glass doesn’t affect food or drink flavour and is ideal for many consumables. Producing 1 kg of new glass emits about 1.5 kg of CO₂. Recycling glass by melting it down again saves roughly half that amount. Deposit bottles are even more sustainable — a reusable beer bottle can be up to 30 times less harmful to the environment than a disposable one. However, glass is heavy, making transport more energy-intensive.

- Plastic (fossil-based): Depending on the type, 1 kg of plastic emits between 3 and 4 kg of CO₂. It’s lightweight, which helps during transport, but recycling is complex, and its raw material, oil, is fossil. Plastic isn’t biodegradable, meaning it doesn’t decompose in nature. It’s versatile, heat- and moisture-resistant, and airtight, and extremely cheap. In fact, virgin plastic is often cheaper than recycled plastic. The key drawback is the raw material: oil is a long-term carbon store, and once extracted, its carbon enters the atmosphere.

- Cardboard and Paper: Made from renewable resources and recyclable, provided they aren’t contaminated with food residues, plastic, or aluminium coatings. Producing 1 kg of new cardboard emits about 1.2 kg of CO₂, while recycled cardboard emits around 1 kg. Non-recycled cardboard often comes from plantation trees, which can compete with food or natural land use. Still, it’s renewable, new trees can be planted. Recycled cardboard is therefore much better for the environment and can be reused multiple times.

- Metal (tin and aluminium): Steel production requires iron ore, which is energy-intensive, mostly due to fossil fuel use (mainly coal). Reusing scrap steel can save up to 70% of energy — every 1,000 kg of scrap saves about 1,500 kg of iron ore and 500 kg of coal. Around 70% of all metal packaging is steel; the rest is aluminium. Producing new aluminium is far more polluting — 1 kg of aluminium emits about 9 kg of CO₂, compared to 3 kg for new steel. Aluminium is made from bauxite (about 3.7 kg needed per kg of aluminium) and emits harmful substances during production, including fluorine gas, PAHs, and mercury.

The major advantage: aluminium is almost infinitely recyclable without quality loss. Recycling uses up to 20 times less energy than new production. - Biobased and Compostable Plastics: Biobased plastic is made from renewable raw materials such as potatoes, maize or sugarcane, and absorbs CO₂ during growth, resulting in lower emissions than conventional plastic made from petroleum. The drawback is that agricultural land, fertilisers and pesticides are required, which harm the environment

Compostable plastic only breaks down under specific conditions, usually in industrial composting facilities, and often not at home or in nature. Therefore, it is not a solution to littering.

It can be produced from both renewable resources and oil, and usually does not contribute to the quality of compost. Uncertainty about which plastics are truly compostable often leads to sorting errors. Because the production of bioplastics is still relatively in its infancy, more research is needed into biodegradability, the reduction of production costs, standardisation, and the technical qualities required to genuinely replace conventional plastics.

Milieu Centraal (a Dutch environmental information agency) therefore advises avoiding compostable plastics and opting instead for plastics that can be recycled. The problem, however, is that plastic recycling takes place on a much smaller scale than we often think, and “new” plastic remains much cheaper.

Greenwashing in the Packaging Industry

Sustainable packaging choices depend on many factors, yet packaging is also a common source of greenwashing. Misleading or false environmental claims often make companies appear greener than they actually are.

Firstly, as mentioned earlier, packaging generally plays a smaller role in a product’s overall environmental impact — often just five to ten percent. Wrapping a highly polluting product in a “green” package doesn’t make it sustainable. Companies can usually achieve much larger reductions by improving product design or production rather than just the packaging.

“Putting a green label on a highly polluting product doesn’t make it sustainable.”

Secondly, packaging often features false or misleading claims — for instance, “This packaging is made from 100% recyclable material.” This is frequently untrue. In plastic recycling, much material is lost in the process, and many plastics aren’t recycled at all because recycling is expensive while virgin plastic remains cheap. In addition, plastic packaging is often contaminated with food waste or not properly sorted, meaning it never reaches recycling facilities.

In the Netherlands, less than 50% of all plastic packaging is actually recycled, compared to 80–90% for glass and cardboard.

Plastic out, everything in cardboard!

It sometimes feels like we’re entering a “paper transition”. Plastic packaging is increasingly replaced by paper under the guise of sustainability. That may look green, but it isn’t always so. Many paper packages aren’t made from 100% paper. Your supermarket bread bag, for instance, often contains a thin layer of plastic. The same goes for liquid packaging (milk, juice, yoghurt), which usually includes an inner plastic or aluminium coating. These layers make them unrecyclable and increase their production impact. Consumers think they’re making a sustainable choice, but that’s misleading.

If you’re a producer looking to improve your packaging impact, carefully consider its design — can it be recycled effectively?

Properties of the right packaging

It’s also vital to understand what a package actually does. Different materials have unique properties that can improve a product’s sustainability, for example, by extending shelf life or protecting goods during transport. Plastic, for instance, often performs better than paper for moisture- or fat-containing products, and it’s lightweight, making logistics more efficient. Aluminium, on the other hand, offers excellent barriers against light, oxygen, and odour, and is less fragile in transport — ideal for long-lasting products travelling long distances.

Choosing the right packaging goes beyond material alone, it’s about functionality in relation to the product. No packaging type is inherently good or bad. The right choice can significantly enhance sustainability by reducing waste, extending shelf life, and enabling more efficient transport, all direct benefits of well-designed packaging.

Conclusion: a nuanced role with direct opportunities

So, what role does packaging truly play in a product’s environmental impact? The answer is nuanced. Packaging’s direct impact is often modest compared with production and use — yet it remains crucial. A well-chosen package can prevent waste, for example by extending shelf life — and the avoided waste often outweighs the packaging’s own footprint.

Packaging design also matters: using less material, improving reusability, and enabling recycling all increase sustainability.

To make informed decisions, we ask ourselves three questions:

- Can we use less packaging?

- Can the design be improved for reuse or recycling?

- Can we use renewable, sustainably sourced materials?

A data-driven approach, such as a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), helps answer these questions objectively. An LCA shows where the biggest impacts occur and supports the development of a packaging strategy that truly contributes to sustainability.

The Hedgehog team helps businesses conduct thorough LCA analyses, so they can take targeted and effective steps towards more sustainable packaging.