For professionals in the sustainability sector, it is important to have a sharp understanding of the distinction between carbon neutral and net zero. Both terms tell a completely different story about an organisation's ambitions and methods. Much confusion arises due to a lack of proper knowledge regarding the definitions. This, whether consciously or unconsciously, encourages greenwashing. In this article, we compare the two terms and clear up that confusion.

What is Carbon Neutral?

Generally, a company speaks of Carbon Neutrality when the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted by a product or activity is balanced by the amount it removes from the atmosphere or offsets. Although this sounds good on paper, there is a catch: the term says nothing about an actual reduction in its own emissions.

Essentially, carbon neutrality means the net impact on the climate is zero. This can be achieved through a combination of reduction and offsetting. This offsetting comes in the form of carbon offsets or carbon credits. These are investments in projects that, in theory, should store carbon or extract it from the atmosphere by, for example, planting trees.

In theory, a company can continue polluting practices as long as it invests in, for instance, reforestation projects to balance the scales. Imagine a company emits 100 tonnes of CO2 and wants to be carbon neutral. The company can choose to reduce its emissions, but it can also choose to buy carbon credits worth 100 tonnes of CO2. It can thus offset its entire emissions without reducing emissions at all.

Standards and hierarchy

Nowadays, much discussion has arisen regarding the term carbon neutral. What was permitted and what was not? To ensure companies do not simply maintain their own interpretation, international standards such as the ISO standard apply a clear hierarchy for the method behind achieving carbon neutrality:

- First Quantify: Accurately measure the footprint.

- ...then Reduce: Lower its own emissions wherever possible.

- ...finally Offset: Cover the remaining emissions with offsets.

The EU takes action

Although current ISO standards are stricter than predecessors like PAS 2060, the fundamental point remains: a company can achieve 'neutral' status without a minimum mandatory reduction occurring in its own chain, which naturally draws criticism.

This criticism is now being converted into legislation: from September 2026, the new EU directive prohibits claims such as "carbon neutral" and "climate neutral" if these are based solely on offsetting. This is described in the renewed Empowering Consumers Directive.

Science Based Target initiative

The Science Based Target initiative (SBTi), the global authority on sustainability standards, is also critical of the term carbon neutral. They therefore do not use the term for their validations. The reason is simple: the model is not ambitious enough to limit global warming to 1.5°C as agreed in the Paris Agreements. Furthermore, carbon neutrality focuses only on CO2, often leaving other (much more powerful) greenhouse gases like methane or nitrous oxide out of the picture.

What is Net Zero?

Net Zero is more ambitious and truly focuses on reducing the CO2 emissions of the company or production process. The EU and SBTi use the following definition:

Net Zero occurs when emissions of all greenhouse gases (not just CO2) caused by human activity are brought to an absolute minimum. The remaining, unavoidable emissions are then permanently removed from the atmosphere.

For a company or product, this means minimising emissions as much as possible and offsetting what remains. To be allowed to use the term Net Zero, the SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard sets very strict requirements:

- Significant reduction in emissions: A company must reduce emissions across the entire value chain (Scope 1, 2, and 3) by at least 90% compared to the base year.

- Long term: This goal must be achieved by 2050 at the latest (but preferably sooner).

- Neutralisation: Only the final 10% of emissions may be 'neutralised' through permanent Carbon Removal, not simply by avoiding emissions elsewhere.

The SBTi sets strict requirements to make a Net Zero claim , which are much tougher than those for carbon neutral:

- Scope 1, 2, and 3: Net Zero looks not only at direct emissions but at the entire chain. This includes emissions from suppliers and the use of the product by the consumer (Scope 3). (If you want to read more about scope 1, 2, and 3, check this page).

- All greenhouse gases: Unlike carbon neutral (which often only counts CO2), Net Zero includes all relevant gases, including methane and nitrous oxide. (Read more about greenhouse gases and the greenhouse effect in this article).

+1 - Removal instead of avoidance: For Net Zero, residual emissions may only be addressed via Carbon Removal (actually taking CO2 out of the air, for example through Direct Air Capture). 'Avoidance' projects, such as preventing deforestation elsewhere, no longer count towards the final calculation.

In short: Net Zero forces you to get your own house in order before looking to your neighbours to offset.

A critical look at $CO_2$ offsetting

The major difference is this: Net Zero takes a critical view of CO2 offsetting, whereas it plays a central role in carbon neutrality. But how exactly does carbon offsetting work, and why is it important to look at this critically?

The idea of offsetting (compensation) is simple: you emit CO2, but you pay to remove or prevent the same amount of CO2 emission elsewhere. As proof of this, you purchase emission rights in the form of a carbon credit (one credit represents one tonne of $CO_2$):

This can be done in two ways: You buy 'tradable' rights on the carbon market. In effect, a company sells you the carbon rights that it is not using. This gives your company more credits to emit.

The other way is by directly obtaining carbon credits through an investment in a project that avoids CO2 (such as a wind farm) or removes it (such as planting a forest). Both are in fact administrative ways to write off the carbon that your company emits.

There are two major gaps in this system that we cannot ignore. On the free market, credits become a kind of medium of exchange. Because credits are often resold, it is difficult for a company to verify whether that saving still actually exists years later. Furthermore, companies are not incentivised to make their production processes more sustainable because they can buy off their emissions from a company that happens to emit less CO2.

The transparency of climate projects is also increasingly being called into question. It is often impossible to prove whether a project truly ensures less CO2. Protecting a forest that was already there, for example, does not pull any extra CO2 from the air. Things also often go wrong with tree planting: young trees absorb hardly any CO2 in the first few years, and if they are destroyed by a forest fire, all the stored CO2 is released again immediately. The compensation is then gone in one fell swoop. Therefore, there is no question of a net emission reduction here either—even though that is exactly what is needed right now.

This does not mean that all climate projects are useless. On the contrary! Many projects are wonderful for biodiversity, soil quality, or the local water supply. They truly make the world a slightly more beautiful place. But as an instrument to simply 'cross out' your own pollution on paper, it is a shaky system.

What are the biggest differences?

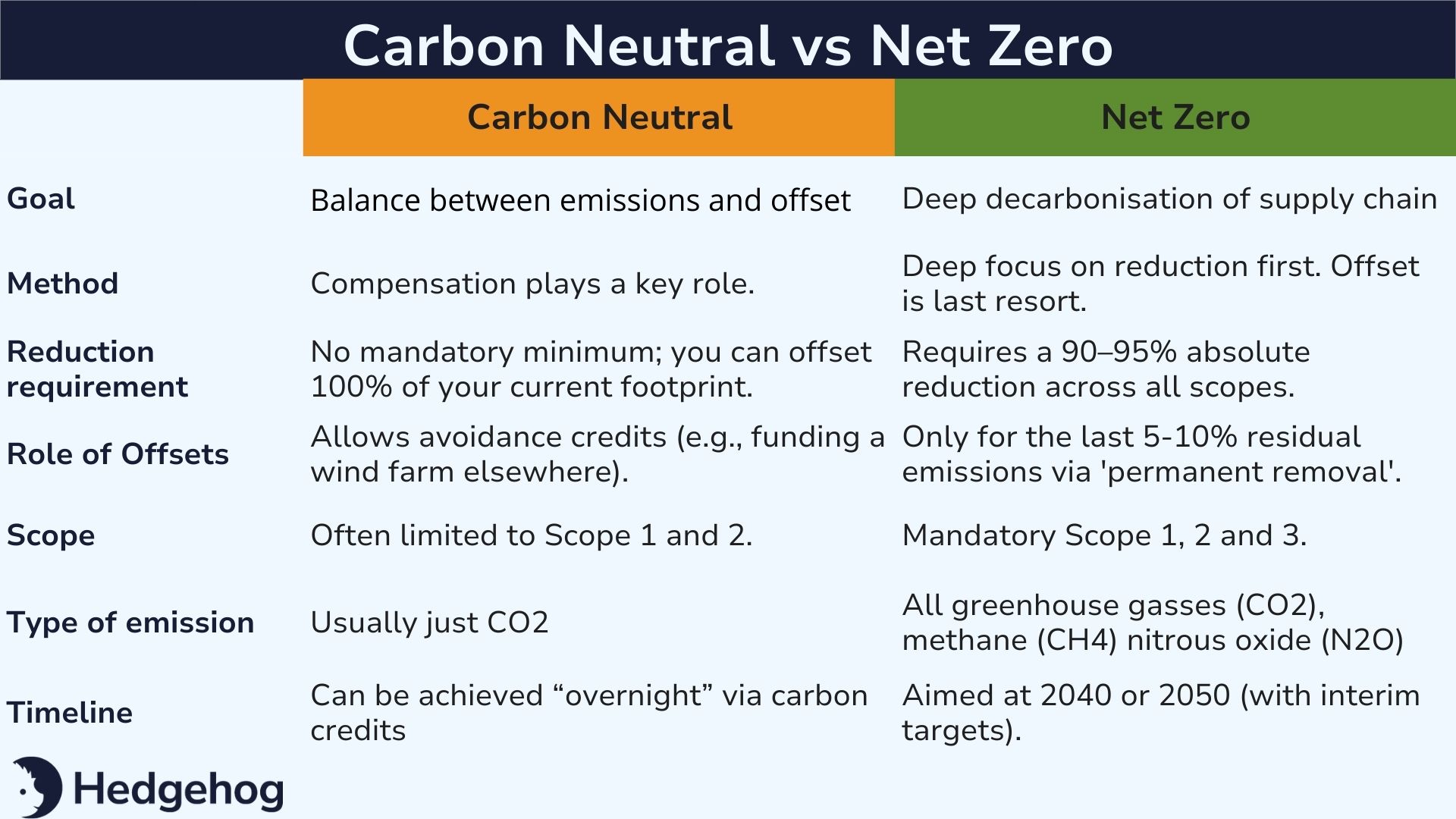

In summary: the differences between the two lie in both the objective and the methodology applied. The key differences can be found in the scope, the method, and the timeline. Furthermore, it is important to understand the differences in impact that the two methods have. With carbon neutral, it remains unclear if and how many greenhouse gases are truly avoided, whereas Net Zero requires a minimum reduction of 90%.

The most important differences at a glance:

1. Reduction versus compensation

In Carbon Neutrality, the emphasis is on the balance. If you emit 100 units and purchase 100 units of credits, you are neutral. According to current definitions, the production process itself does not have to change. With Net Zero, reduction is the main component. You must adjust your process until you emit almost nothing. Compensation is merely the final piece for that which is technically impossible to reduce.

“Compensation is merely the final piece for that which is technically impossible to reduce.”

2. Scope 3: Chain responsibility

Many claims for carbon neutrality are limited to Scope 1 (direct emissions) and Scope 2 (energy consumption). The complex Scope 3, which often accounts for 80% to 90% of the actual impact (such as purchased materials, transport, and the use of products by customers), is often made optional in carbon neutrality. For a net zero target according to SBTi guidelines, including the full Scope 3 is a mandatory requirement.

“Including the full Scope 3 is a mandatory requirement”

3. The type of credits

Under carbon neutrality, you may (according to current definitions) use ‘avoidance credits’ — projects that prevent more emissions from being added (such as protecting a forest that was threatened by deforestation). With net zero, only removal credits are accepted in the final phase. These are projects that actively extract CO2 from the air and store it for hundreds of years.

However, with the introduction of the new EU directive (Empowering Consumers Directive), from September 2026, it will no longer be permitted to use avoidance credits in connection with carbon neutrality. Consequently, companies here too must shift their focus from ‘buying off’ emissions elsewhere to actual reduction and certified carbon removal within their own chain.

Minimise your emissions

Hedgehog advises avoiding the term ‘carbon neutral’. It provides no clear insight into how much CO2 emissions a company is actually actively reducing. Moreover, the term is far too susceptible to greenwashing and deception.

If you truly want to contribute as little as possible to climate change as a company, go for net zero. You then organise your business operations in such a way that emissions are limited to an absolute minimum. During the transition phase to Net Zero, you can certainly make use of offsetting, but do so with an intention that goes beyond just a calculation.

Instead of seeking the cheapest credits just to be allowed to apply a 'neutral' label, we at Hedgehog recommend investing in projects that restore nature and biodiversity. Choose projects that give back to ecosystems what we have destroyed over recent decades. Think of restoring wetlands, regenerative agriculture that locks carbon in the soil, or restoring damaged coral reefs. These types of projects not only offer a climate benefit but also strengthen the planet's resilience. To find out more, please view our offsetting page.

At Hedgehog, we support you in this process with our Carbon Platform and our expertise in the field of Science-based targets. We help you find your way through the forest of definitions, measure your footprint accurately, and draw up a reduction plan that truly makes an impact.

The transition from 'neutral on paper' to 'net zero in practice' is a challenge, but it is also an opportunity to set the standard as a leader in the sustainability sector. Let’s stop using offsetting as an excuse and start using transformation as a strategy.